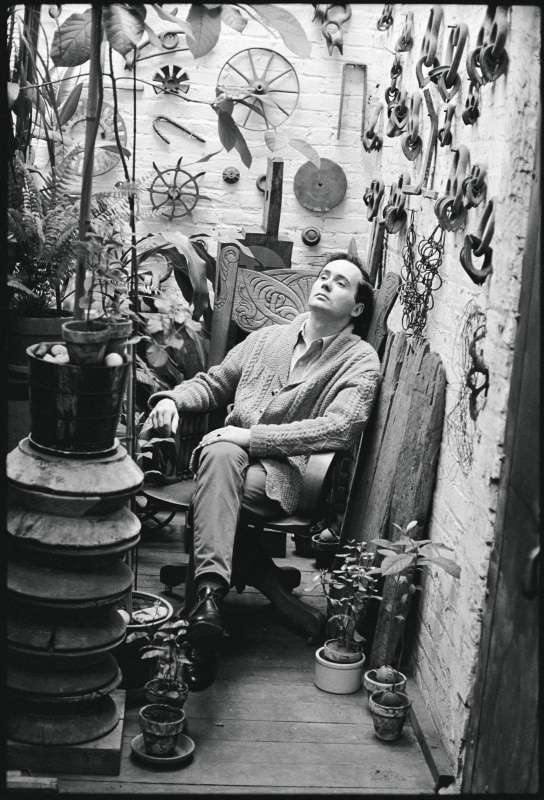

Robert Indiana sitting in the plant room at his Coenties Slip studio. Photo: © William John Kennedy. Image courtesy of KIWI Arts Group

One of the preeminent figures in American art since the 1960s, Robert Indiana played a central role in the development of assemblage art, hard-edge painting, and Pop art. Indiana, a self proclaimed “American painter of signs,” created a highly original body of work that explores American identity, personal history, and the power of abstraction and language, establishing an important legacy that resonates in the work of many contemporary artists who make the written word a central element of their oeuvre.

Robert Indiana was born Robert Clark in New Castle, Indiana on September 13, 1928. Adopted as an infant, he spent his childhood moving frequently throughout his namesake state. His artistic talent was evident at an early age, and its recognition by a first grade teacher encouraged his decision to become an artist. In 1942, Indiana moved to Indianapolis in order to attend Arsenal Technical High School, known for its strong arts curriculum. After graduating he spent three years in the U.S. Air Force and then studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Skowhegan School of Sculpture and Painting in Maine, and the Edinburgh College of Art in Scotland.

In 1956, two years after moving to New York, Indiana met Ellsworth Kelly, and upon his recommendation took up residence in Coenties Slip, once a major port on the southeast tip of Manhattan. There he joined a community of artists that would come to include Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, and Jack Youngerman. The environment of the Slip had a profound impact on Indiana’s work, and his early paintings include a series of hard-edge double ginkgo leaves inspired by the trees which grew in nearby Jeannette Park. He also incorporated the ginkgo form into his nineteen-foot mural Stavrosis (1958), a crucifixion pieced together from forty-four sheets of paper that he found in his loft. It was upon completion of this work that Indiana adopted the name of his native state as his own.

Indiana, like some of his fellow artists, scavenged the area’s abandoned warehouses for materials, creating sculptural assemblages from old wooden beams, rusted metal wheels, and other remnants of the shipping trade that had thrived in Coenties Slip. While he created hanging works such as Jeanne d’Arc (1960–62) and Wall of China (1960–61), the majority were freestanding constructions which Indiana called “herms” after the sculptures that served as boundary markers at crossroads in ancient Greece and Rome. The discovery of nineteenth-century brass stencils led to the incorporation of brightly colored numbers and short emotionally charged words into these sculptures as well as canvases, and became the basis of his new painterly vocabulary.

Indiana quickly gained repute as one of the most creative artists of his generation, and was featured in influential New York shows such as New Media—New Forms at the Martha Jackson Gallery (1960), Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art (1961), and the International Exhibition of the New Realists at the Sidney Janis Gallery (1962). In 1961, the Museum of Modern Art acquired The American Dream, I (1960–61), the first in a series of paintings exploring the illusory American Dream, establishing Indiana as one of the most significant members of the new generation of Pop artists who were eclipsing the prominent painters of the New York School.

Although acknowledged as a leader of Pop, Indiana distinguished himself from his Pop peers by addressing important social and political issues and incorporating profound historical and literary references into his works. American literary references appear in paintings such as The Calumet (1961) and Melville (1961), exhibited in 1962 in Indiana’s first New York solo exhibition, held at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery. In 1964 Indiana accepted Philip Johnson’s invitation to design a new work for the New York State Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, creating a twenty–foot EAT sign composed of flashing lights, and collaborated with Andy Warhol on the film Eat, a silent portrait of Indiana eating a mushroom in his Coenties Slip studio. His first European solo exhibition took place in 1966 at Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf, Germany, and featured his Number paintings (1964–65), a series of works on a theme that he has explored in various formats throughout his career.

Read Full Biography at www.robertindiana.com

Read Chronology at www.robertindiana.com

Invert